S2E3 Long Distance

nb. descriptive hyperlinks connect to timestamped moments in the video above

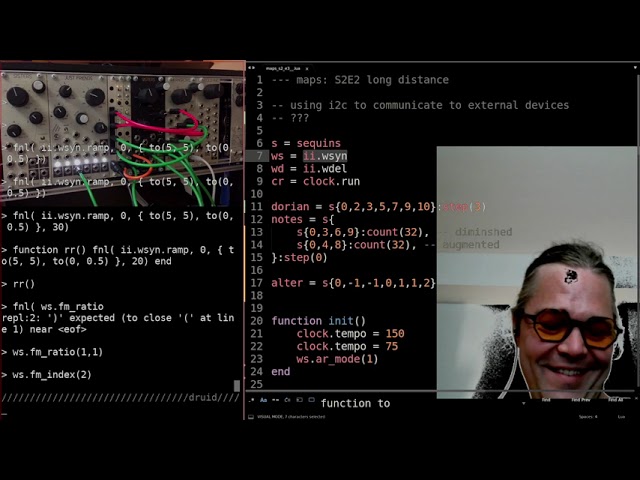

within the episode, Trent executes crow commands via druid on the left side of the screen while taking longform notes in a text editor on the right side of the screen.

this episode begins with a function-centric adaptation of ASL, a core feature of crow which was demonstrated in the previous episode. if this doesn’t sound familiar please feel free to hop back in time – the second half of the writeup is heavily focused on ASL (making shapes and onward).

review: clocks

crow 3.0 repackaged the norns clock system for tempo-synced execution of events. it’s super powerful + flexible, but there can be a bit of a rough onboarding if you’re unfamiliar with it.

essentially, there is a wall clock from which we can either sync events to occur (at different rates), or which we can sleep to delay the processing of an event. when we spawn a function that’s aware of the clock, we call it a “coroutine”. we can use both methods (sync and sleep) simultaneously, though the general approach is:

- for musical-time purposes use

clock.sync, which accepts a beat division to which it should sync - for timed delays use

clock.sleep, which accepts a seconds-based duration to hold before execution

creating a musical-time clock

we can create a clock-synced coroutine on a single line of code. we’ll begin by aliasing the required clock.run as cr, then we’ll build a synced function (output 1 = v/8 from dorian scale):

> cr = clock.run

> dorian = sequins{0,2,3,5,7,9,10}:step(3)

> cr(function() while true do clock.sync(1) output[1].volts = dorian()/12 end end)

basic anatomy of the cr function:

while true do: our events will loop continuously until the canceled coroutine is canceledclock.sync(1): sync to the next-nearest “1” beat division, then execute the code that follows

clock.sync is an important component of the coroutine – without it, crow will try to run an infinite number of events instantaneously, which will time out the CPU.

also:

clock.cleanup()will clear your currently-running clock coroutines.clock.tempowill allow you to set the global tempo

funnel (fnl): making changes without touching knobs

to start the educational part of the episode, Trent introduces fnl, a custom function which borrows the concept of ASL and applies it to function generation.

in the first example, Trent uses fnl to to increase the clock tempo from 120 to 480 over a period of 31.4 seconds:

> fnl( function(tempo) clock.tempo = tempo end, 120, { to(480, 31.4) } )

basic anatomy of the fnl function

- a function which we want to feed slewed values

- our starting value

- a table which contains tables (nested tables!!) of destination values and the duration we want the journey to take (in seconds)

- in the example, Trent uses ASL’s

toconstruct to represent these values, because of how conceptually similarfnlis to ASL – you can just as easily swapto(480, 31.4)with{"TO", 480, 31.4}

- in the example, Trent uses ASL’s

- frame rate (optional, default is 15fps)

curious about the guts? here’s Trent’s overview and here’s the source code.

over i2c

ramp

next, Trent walks us through addressing w/synth parameters using fnl and i2c:

> fnl( ii.wsyn.ramp, 0, { to(5,5), to(0,0.5) }, 20 )

this will affect the shape of the w/synth by adding 5V to the ramp parameter incrementally over 5 seconds, then back down to 0 in a half-second. Trent specifies 20fps, to help round out the voltage changes.

let’s assign it to a function which can be called more easily:

> function rr() fnl( ii.wsyn.ramp, 0, { to(5,5), to(0,0.5) }, 20 ) end

now we can just execute rr() in the repl to get our ‘rising ramp’ on command.

(the definition of mapcore expands)

fm_ratio

let’s target another w/synth parameter: the FM ratio.

> fnl( ii.wsyn.fm_ratio, 1, { to(11,7), to(3/2,2) } )

this will affect the FM ratio by sliding it up to 11/1 over 11 seconds, then back down to 3/2 in 2 seconds. but there’s also some fun to be had in changing the frame rate of this fnl, for example:

> fnl( ii.wsyn.fm_ratio, 1, { to(11,7), to(3/2,2) }, 7 )

…produces quite a different effect than the default 15fps!

to make it easier to pass the frame rate into the fnl, let’s assign it to a function which can accept frame rate as an argument:

> function rf(fps) fnl( ii.wsyn.fm_ratio, 1, { to(11,7), to(3/2,2) }, fps ) end

now, we can execute rf(6) to generate our FM modulator at 6fps!

running in tandem

a performance gesture emerges:

> rf(6)

> rr()

> rr()

> rf(3)

> rr()

> rr()

> rr()

> rr()

> rf(4)

> rr()

Matryoshka

Trent navigates around the buffer.

fnl can be used to modulate functions which require more than one argument by nesting the target function inside of another function with the single argument we wish to funnel.

eg. if we wanted to advance a tiny playback window through a frozen delay line:

fnl(

function(pos)

ii.wdel.cut(pos*255,255)

ii.wdel.length(1,8)

end,

0,

{ to(1,32) },

2

)

this is a bit of a mouthful, but essentially:

- we want to modulate the numerator of

ii.wdel.cut(num,denum)to advance the playback window start point - we need to re-define the length of the delay line after making this change, so our end point moves along with our start point

- so, we wrap both into a function!

formatted as a single line for easy execution in druid:

> fnl( function(pos) ii.wdel.cut(pos*255,255); ii.wdel.length(1,8) end, 0, { to(1,32) }, 2 )

after Trent uses this mechanism to modulate the loop window while recording, they open up the loop length to reveal the collage and execute a gorgeous performance.

focusing on the destination

Trent’s holy grail of performance.

fnl / funnels allow the performer to define an end-point and describe the journey without needing to manually execute the journey themselves. this is why funnels are described as ‘a slope language for functions’ – not just LFOs which automate a looping gesture, but a realtime automation brewed up in the moment to arrive at a desired future.

rather than “holding a knob and turning it down very slowly”, try using a funnel!