S2E2 Zippers

nb. descriptive hyperlinks connect to timestamped moments in the video above

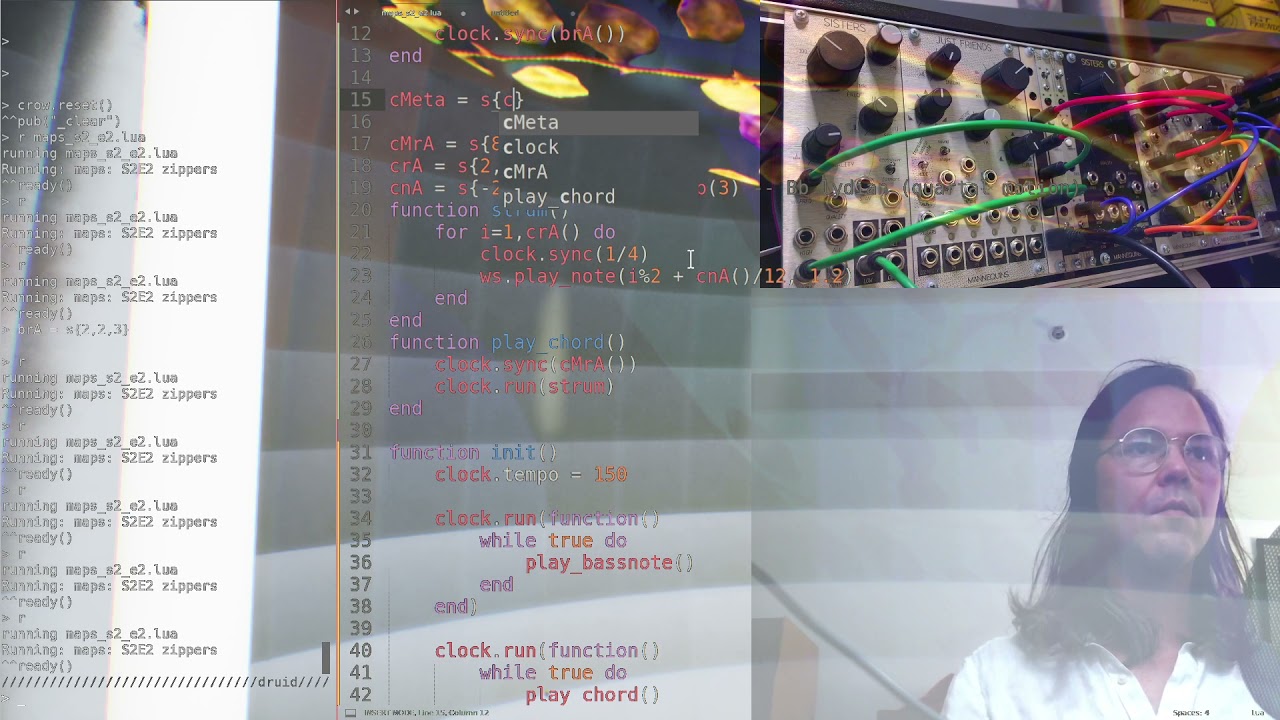

within the episode, Trent executes crow commands via druid on the left side of the screen while taking longform notes in a text editor on the right side of the screen.

- use the output scale functionality of crow to write melodies by describing contours

this episode focuses a lot on sequins, the library which was explored in episode 1. if you need (re-)familiarizing, make sure to check out the previous episode!

to start, Trent shorthands sequins so we don’t have to write 7 characters every time we want to employ the sequins library. since sequins is a globally known library inside of crow, we can simply assign a variable s to all of its functions:

s = sequins

review: sequins are sequences of anything

the fundamental technique that Trent employed during the opening performance is using sequins to describe both rhythms and pitches.

throughout the episode (as well as within the monome + whimsical raps ecosystem) we’ll use numbers to describe semitone (12TET) distance from some base pitch, 0. for digital oscillators like Just Friends or w/’s synth mode, 0 corresponds to C. so -5 = G, -2 = B-flat.

since the basic operation of sequins is:

- define a collection of values and assign it to a meaningful name

- ping the meaningful name to return a single entry from the collection and advance the index

…we can sequence most anything in our code! the number of times we should repeat an action, the beat interval we’d like to sync to, which notes to play, etc.

to illustrate how this works, try queueing up the following code:

s = sequins

repetitions = s{3,5,7}

notes = s{9,5,7,0,14,2}

steps = s{2,1,-2,3}

rhythms = s{1/4,1/3,1,1/2,1/6}

function arp(sync_value)

for i = 1,repetitions() do

clock.sync(sync_value)

output[1].volts = notes()/12

output[2](pulse())

end

notes:step(steps())

go()

end

function go()

seq = clock.run(arp,rhythms())

end

function stop()

clock.cancel(seq)

end

and execute go() in druid to start. execute stop() in druid to stop.

structure:

repetitionsgets used to determine the number of notes in an arpeggio and the number of timesnotesis iteratednotesholds our notes which we’d like to hear, written as semitones from a base pitch of0stepsis used to change the way ournotesare iterated (one step at a time is the default)rythmsprovides our sync values for the clock coroutine

each time we call any sequins function, it returns a value. we can use that value to do sequence anything in our code.

start simple

there’s quite a bit of magic at play in Trent’s explanation of the performance – but if you feel like you’re getting at all lost, feel free to cut to where Trent begins rewriting the code from the base-up

Trent uses crow output 1 to control v/8 on an oscillator.

let’s start with some foundational code to execute in druid (just do it in real-time via the command line):

> output[1].volts = 0

> output[1].scale = 'none'

> output[1].slew = 1

> output[1].volts = 1

and you’ll hear the pitch of your oscillator gently slide up an octave. crow has exceptionally smooth digital to analog converters, so let’s add some steppiness:

> output[1].scale({0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11})

> output[1].volts = 0

now, you’ll hear discrete semitones as crow makes its way from 0V to 1V.

let’s try some other semitone scales (you can choose to leave the parentheses on or off):

> output[1].scale{0,2,5,7,9}

> output[1].volts = 1

> output[1].volts = 0

> output[1].volts = 2

> output[1].volts = -5

> output[1].volts = 0

if you do it a lot, make it a function

Trent starts building a script

now that we know this sort of gesture is fun, let’s commit the scaffolding to a script so we can just do the fun thing:

function init()

output[1].slew = 1

output[1].scale{0,2,5,7,9}

output[2].action = ar(0.1, 5) -- for extra expressiveness, patch output 2 to a VCA

end

function nv(v)

output[1].volts = v

output[2]()

end

now, we can just execute nv(1) in druid to assign output 1 to 1V and initiate the envelope on output 2!

making shapes

Trent uses Blue in Green as inspiration, because the composition has a definitive shape. today’s challenge is to describe these slopes in code!

crow has a slope language (referred to as ASL) built into it. let’s use it to describe a voltage journey, which will be quantized to our previously-established scale (if you cleared it, just execute output[1].scale{0,2,5,7,9}):

> output[1]{to(1,0), to(0,3), to(0.9,0.1)}

> output[1]( loop{to(1,0), to(0,3), to(0.9,0.1)} )

> output[1].volts = 0

to has three components: destination voltage, time to get there, shape to describe the journey. more info here.

let’s try changing the shape of that last stage:

> output[1]( loop{to(1,0), to(0,3), to(0.9,1,'exp')} )

sequencing chunks

watch Trent encounter a new problem (ERROR: no stages left)

as Trent mentions, stacking many to’s is not a very efficient way to compose an entire piece – but we can sync execution of ASL chunks to our clock!

sidebar: clock construction tip

so far, we’ve initiated clocks using this construction:

function something_to_do()

while true do

clock.sync(some_beat_value)

-- stuff gets done

end

end

clock.run(something_to_do)

however, setting up a separate corresponding function isn’t a strict requirement of clock invocation – we can just wrap a function into the invocation itself:

clock.run(function()

while true do

clock.sync(some_beat_value)

-- stuff gets done

end

end)

bundling our movements

rather than queue up a lot of to statements (which eventually leads to the ERROR: no stages left which Trent runs into), we can collect the segment descriptions into a single table and iterate through it using sequins:

stages = sequins{ {1,0}

, {0,3}

, {0.9, 1, 'exp'}

-- line 2

, {-0.2, 0}

, {-0.5, 0.5}

, {0.7, 0.5}

, {0, 2}

-- line 3

, {0.7, 0}

, {0.1, 1}

, {0.6, 0}

, {0.4, 1}

, {1.2, 0}

, {0.8, 1}

}

so if we pass a stages() call to a variable, that variable will be assigned the value of the table at the current index:

> stage = stages()

> print(stage[1], stage[2]}

1 0

> stage = stages()

> print(stage[1], stage[2]}

0 3

> stage = stages()

> print(stage[1], stage[2]}

0.9 1

here’s how our script could look:

function init()

output[1].scale{0,2,5,7,9}

output[2].action = ar(0.1, 5) -- for extra expressiveness, patch output 2 to a VCA

end

stages = sequins{ {1,0}

, {0,3}

, {0.9, 1, 'exp'}

-- line 2

, {-0.2, 0}

, {-0.5, 0.5}

, {0.7, 0.5}

, {0, 2}

-- line 3

, {0.7, 0}

, {0.1, 1}

, {0.6, 0}

, {0.4, 1}

, {1.2, 0}

, {0.8, 1}

}

function big_melody2()

output[2]()

clock.run(function()

while true do

local stage = stages() -- pass the currently-indexed table to 'stage'

output[1].slew = stage[2]/2 -- the second entry describes time

output[1].volts = stage[1] -- the first entry describes voltage

if stage[3] then -- if there's a third entry, for shape...

output[1].shape = stage[3] -- change the output shape!

else -- otherwise...

output[1].shape = 'linear' -- keep it linear

end

clock.sleep(stage[2]) -- the second entry describes time

end

end)

end

if you want the melody to be tempo-synced, you could replace clock.sleep with clock.sync, but be mindful that clock.sleep accepts a time interval in seconds whereas clock.sync accepts a time interval in beats, eg:

clock.sleep(1) -- hold for 1 second

clock.sync(1) -- hold for the next-nearest whole beat

so, you may find that clock.sync requires additional math to get the right feel – this is why Trent decides on clock.sync(stage[2] * 2).

where to go from here?

there’s lots to explore!

- Trent adds a

stretchvariable to stretch + shrink the melody - Trent adds an

offsetvariable to shift the melody - Trent changes the quantization scale as the script is playing

- Trent inserts new quantization scales directly into the

sequins

doing it with dynamic shapes

rather than rely on this explicit description of movement, Trent closes the episode with a shape-based approach.

when we were running the ASL code above, the movement descriptors were fixed – we couldn’t dynamically change one of the stages without re-running the code. but it’s totally possible to make these variables unfixed, using dyn!

try running this script:

function init()

output[1].scale = {0,2,3,5,7,8,10}

output[2].action = ar(0.1, 5)

output[1](loop{ to(0,0)

, to(dyn{height=1},1)

})

end

and in druid, live-execute:

> height = 1.2

> height = 1.3

> height = 1.8

> height = 2

> height = -1

fun, right? these changes can lead to some very nice sequences.

dyn variables also accept special modifications which make it a lot easier to explore!

:step

:step is a dyn modifier which auto-increments the dyn’s starting value through addition each time it cycles.

try running this script:

function init()

output[1].scale = {0,2,3,5,7,8,10}

output[2].action = ar(0.1, 5)

output[1](loop{ to(0,0)

, to(dyn{height=0.2}:step(0.1),1)

})

end

you should hear that the sequence linearly adds more notes into the sequence, as height is incremented by 0.1 every second.

:mul

:mul is a dyn modifier which auto-increments the dyn’s starting value through multiplication each time it cycles.

try running this script:

function init()

output[1].scale = {0,2,3,5,7,8,10}

output[2].action = ar(0.1, 5)

output[1](loop{ to(0,0)

, to(dyn{height=0.2}:mul(1.5),1)

})

end

you should hear that the sequence adds more notes into the sequence, as height is multiplied by 1.5 every second.

:wrap

:wrap affects modifiers like :step and :mul by allowing you to window their influence to ranges which you find compositionally useful.

nb. :wrap takes two arguments – a floor value and a ceiling value.

try running this script:

function init()

output[1].scale = {0,2,3,5,7,8,10}

output[2].action = ar(0.1, 5)

output[1](loop{ to(0,0)

, to(dyn{height=0.2}:mul(1.5):wrap(0.2, 5),1)

})

end

you should hear that the sequence adds more notes into the sequence, as height is multiplied by 1.5 every second, but instead of infinitely adding it will wrap the height back to 0.2 after it reaches 5.

all together now

try running this script for an evolving sequence:

function init()

output[1].scale = {0,2,3,5,7,8,10}

output[2].action = ar(0.1, 5)

output[1](loop{ to(dyn{base=0}:step(-0.2):wrap(-2,3),0)

, to(dyn{height=0.2}:mul(1.5):wrap(0.2, 5)

,dyn{time=1})

})

end

some final thoughts from Trent

bonus: ASL oscillator!

after the episode, Trent shared a special example of how ASL can be used to generate oscillators through crow’s outputs. this results in lovely, bitcrushed triangle-ish sine-like timbres that should inspire hours of play :)